Trying to think like a compiler, Part 2

(This post is part of a series on the subject of my hobby project, which is recreating the C source code for the 1989 game F-15 Strike Eagle II by reverse engineering the original binaries.)

Nothing terribly exciting happened since the last post. I am (slowly) porting START.EXE functions from assembly to C one by one, doing some additional research using IDA and the dosbox debugger to figure out what specific routines do at the same time. The game is still not runnable, but I’m making progress.

One thing that changed is that I’ve made a lst2ch.py script to convert the listing output of IDA into a C header and source file. That way, whenever I rename routines or variables in IDA, I do not need to carry them over into the header file manually - the header file is now autogenerated. I still need to rename stuff in my source files manually, at least for now, but at least it gives me an autocomplete on all routines and data objects. The source file contains definitions for all the data, with the eventual goal of eventually moving it into C - I’m linking with an autogenerated assembly object that has my ported routines automatically removed for now.

I have also implemented some statistics into the script which show me how much work remains to be done:

ninja@dell:eaglestrike$ make start tools/lst2ch.py lst/start.lst src/f15-se2 conf/start_rc_conf.py --noc Writing C header file: src/f15-se2/start.h Found routines: total: 247, ignored: 53, remaining: 194, ported: 23, need porting: 171 Accumulated routines' size: remaining: 21638/0x5486/100%, ported: 4198/0x1066/19.4%, need porting: 17440/0x4420/80.6% Found 1013 variables, size = 31504/0x7b10 [...]

The 53 ignored routines are those from the C library and the single-instruction far jump trampoline routines invoking code from the driver overlays. That leaves us with 194 routines to rewrite, either into C or assembly (some of the game’s routines were obviosly written in assembly and hence are impossible to match exactly from C) with hardcoded numerical offsets resolved into correct data and code references. As evident from the output, I have completed 23 routines, totaling around 4KB of code, which amounts to slightly below 20% of the total work - for the first executable alone! Well, nobody said this was going to be quick or easy.

I also made a vga2bmp.py script to turn binary data dumps from the Dosbox debugger into bitmaps, with customizable size and palette. One thing is good for is figuring out what various drawing routines do; I place a breakpoint on a routine, do a memdumpbin a000:0 fa00 in the debugger to dump the contents of video RAM to a file, step over the function, dump again, then run the script on the “before” and “after” dump to see what changed on the screen. Or modify the value of a routine argument before it is pushed onto the stack, then trigger the routine and see what the argument controls. Here for example I am figuring out the (x,y) coordinate arguments of the drawString routine:

Another thing it can do is display arbitrary data as pixels - I was hoping to see font or some other visual data in either START.EXE or the video driver overlay, but unfortunately that wasn’t the case. Makes for an interesting visual gimmick though:

Gee, that’s a lot of zeros. Also the driver jump trampolines are visible as regular brown dots for 0xEA far jump opcodes if you strain your eyesight.

In any case, today I wanted to go over some… interesting examples of assembly code that I encountered on my voyage, and the C code they ended up resolving into. So let’s jump into it.

Keeping the numbers up in the air

I encountered this in the routine I ended up calling missionSelect. It pops up the briefing board with the guy pointing his arm at it as seen above, and lets the player choose the difficulty and the scenario. This particular bit handles the case where the “Other scenario” option was selected to go into a submenu which lets the player pick missions from the Desert Storm scenario disk. The game is going over a hardcoded array of scenario filenames, trying to fopen() them, and setting a flag in an array for those that were found:

startCode1:0781 selectedOther:

startCode1:0781 mov [bp+count], 4

startCode1:0786 mov [bp+index], 0

startCode1:078B jmp short otherIter

startCode1:078D otherNext:

startCode1:078D inc [bp+index]

startCode1:0790 otherIter:

startCode1:0790 cmp [bp+index], 4

startCode1:0794 jge short checkOther

startCode1:0796 mov bx, plh3d3Ptr

startCode1:079A mov si, [bp+index]

startCode1:079D shl si, 1

startCode1:079F mov si, scenarioCodePtr[si]

startCode1:07A3 mov al, [si]

startCode1:07A5 mov [bx], al

startCode1:07A7 mov bx, plh3d3Ptr

startCode1:07AB mov si, [bp+index]

startCode1:07AE shl si, 1

startCode1:07B0 mov si, scenarioCodePtr[si]

startCode1:07B4 mov al, [si+1]

startCode1:07B7 mov [bx+1], al

startCode1:07BA mov ax, offset aRb_1 ; "rb"

startCode1:07BD push ax

startCode1:07BE push plh3d3Ptr

startCode1:07C2 call _fopen

startCode1:07C5 add sp, 4

startCode1:07C8 mov fileHandle, ax

startCode1:07CB cmp ax, 1 🔴🔴🔴 ???

startCode1:07CE sbb cx, cx 🔴🔴🔴 ???

startCode1:07D0 neg cx 🔴🔴🔴 ???

startCode1:07D2 mov bx, [bp+index]

startCode1:07D5 mov scenarioFoundArr[bx], cl ; place flag in array indicating scenario's presence

startCode1:07D9 or cl, cl

startCode1:07DB jz short otherCont

startCode1:07DD dec [bp+count] ; failed to fopen, decrease avail extra scenario count

startCode1:07E0 otherCont:

startCode1:07E0 push fileHandle

startCode1:07E4 call _fclose

startCode1:07E7 add sp, 2

startCode1:07EA jmp short otherNextThe first eyebrow-raising construct is the cmp-sbb-neg thing. It took me a while, but turns out this is a known idiom for a branchless check to see if a value was NULL or not. If the file handle (which is in AX) is NULL, then cmp ax, 1 (which is essentially a subtraction) will set the carry flag (CF == 1). Next, sbb cx, cx is confusing because we did not put anything in CX, but this is just a way to isolate the value of the carry flag, since it essentially means cx = cx - cx - CF, so ultimately cx = -CF. Last, we use neg cx to get a positive value, and CX becomes 0 if the file handle was originally NULL, and 1 otherwise, but no conditional jump was required. Pretty neat.

The other thing is how the code reuses the register values for things it already calculated to become inputs into the next step. I will spare the reader an account of all the things that I tried, but in the end, the above assembly is matched perfectly by the following C code:

// 0x781

for (count = 4, index = 0; index < 4; index++) { // find extra scenarios

plh3d3Ptr[0] = *scenarioCodePtr[index];

plh3d3Ptr[1] = *(scenarioCodePtr[index] + 1);

// 0x7c2

if ((scenarioFoundArr[index] = ((fileHandle = fopen(plh3d3Ptr, aRb_1)) == NULL))) count--; // 😵😵😵

// 0x7e4

fclose(fileHandle);

}If you asked “who writes code like this?!”, then I feel you more than you know, but in this case I can understand the developers. Compilers of that era were primitive, and breaking up the complicated expression to write the result into a variable would result in emitting code which does a data write, then a read of that same data to use in the next expression (guess how I know). The dev was trying to keep the numbers dancing in the registers as long as possible to avoid incurring a performance hit. This would not matter with a modern compiler, but it just shows what hoops they needed to jump through back in 1989.

Non-orthogonal BS

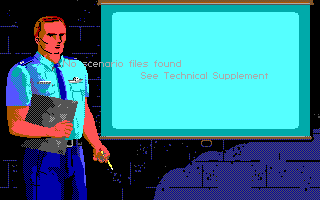

Moving on but still in the same routine, here’s a seemingly innocuous series of conditional checks and jumps:

startCode1:0876 les bx, gameData

startCode1:087A cmp word ptr es:[bx+COMM_BUFFER_THEATER], 6 ; 6 == desert storm

startCode1:087F jz short checkDifficulty

startCode1:0881 jmp out

startCode1:0884 checkDifficulty:

startCode1:0884 cmp word ptr es:[bx+COMM_BUFFER_DIFFICULTY], 4 ; diff 4 is demo mode

startCode1:0889 jz short outThis writes itself:

// 0x876

// show mission type dialog for desert storm

if (gameData->theater == THEATER_DS && gameData->difficulty != DIFFICULTY_DEMO) {

// ...However, no matter what I tried, the jz at 0x889 ended up being turned into an inverse jnz+jmp short:

I have since refactored the code to use structs instead of the FARPTR_CAST_OFFSET ugliness, which is why it’s a little different in the screenshot, but it does the same thing.

I usually write out an entire routine while looking at the disassembly, then tweak it into matching. This usually does not matter because for the most part, the process is orthogonal - changing a source code line only affects the assembly generated at that location. But there are exceptions. Here, because I had mismatching code later on at 0x907, the jump destination was too far for a short jump (+/-0x7f bytes), so the compiler was forced to emit a short-distance jnz instead, followed by a non-short jmp by 0x82 bytes forward. I’ve seen other examples of this, such as the compiler creating storage on the stack for some intermediate values, altering the amount of sub sp, 0x123 done at the entry to a function before the code in question, but it’s fortunately rare. Here, the problem was fixed by getting the code in the loop later to match, which is an interesting problem on its own:

How many ways to write a 3-line loop?

As can (hopefully) be seen in the above screenshot, I’m having problems with this loop code:

startCode1:08C8 selectMission:

startCode1:08C8 mov ax, 4

startCode1:08CB push ax ; select

startCode1:08CC push missionStr ; string

startCode1:08D0 mov ax, offset miss_unk2

startCode1:08D3 push ax ; p2

startCode1:08D4 mov ax, offset miss_unk1

startCode1:08D7 push ax ; p1

startCode1:08D8 call missionMenuSelect

startCode1:08DB add sp, 8

startCode1:08DE mov missionPick, ax

startCode1:08E1 cmp ax, 4

startCode1:08E4 jz short missionIs4

startCode1:08E6 jmp short out

startCode1:08E8 missionIs4:

startCode1:08E8 mov ax, 4

startCode1:08EB push ax ; select

startCode1:08EC push missionStr ; string

startCode1:08F0 mov ax, offset miss_unk4

startCode1:08F3 push ax ; p2

startCode1:08F4 mov ax, offset miss_unk3

startCode1:08F7 push ax ; p1

startCode1:08F8 call missionMenuSelect

startCode1:08FB add sp, 8

startCode1:08FE add ax, 4

startCode1:0901 mov missionPick, ax

startCode1:0904 cmp ax, 8

startCode1:0907 jz short selectMissionI spent 3 days trying to write it out as for/while/do-while, but could not obtain the single jz at the end - somehow it always ended up with a sequence of jz-jmp short-jmp short, with minor variations. Finally the golden ticket for this bit as well as the previous one ended up being this:

if (gameData->theater == THEATER_DS && gameData->difficulty != DIFFICULTY_DEMO) {

// 0x890

scenarioFoundArr[0] = scenarioFoundArr[1] = 0;

// 0x895

scenarioFoundArr[2] = scenarioFoundArr[3] = scenarioFoundArr[4] = 1;

// 0x8ad

if (missionMenuSelect(missType_unk1, missType_unk2, aMissionType, 0) == 0) {

// 0x8c2

nearmemset(scenarioFoundArr, 0, 5);

// 0x8c8

do {

// 0x8d8

if ((missionPick = missionMenuSelect(miss_unk1, miss_unk2, missionStr, 4)) != 4) break;

// 0x8f8

} while ((missionPick = missionMenuSelect(miss_unk3, miss_unk4, missionStr, 4) + 4) == 8);

}

}

} // routine ends herePutting the latter assignment into the loop condition by itself is not something that occured easily, believe me. This is an another example of the intermediate value reuse paradigm as discussed in the first item, although somewhat less extreme.

An another interesting quirk was that the break statement inside the loop cannot be a return even though it ends up going to the routine return anyway. Doing so elided a les bx for the gameData->difficulty value - the one from gameData->theater was reused since it’s the same structure, but the kicker is that the code for the loop and function termination is identical! No idea why it has that effect (an in-line return forcing an evaluation of branch destinations and value propagation along those? It figured out it didn’t need to reload it, but normally it wouldn’t check?), but it’s an another example of “non-orthogonal BS” where later code changes the form of code that comes before it. Huh, I guess they are not that rare after all…

Inlined functions anyone?

For my last trick, I present you this code from a routine which handles player input on the pilot select screen:

startCode1:200E mov si, [bp+var_6]

startCode1:2011 mov cl, 5

startCode1:2013 shl si, cl

startCode1:2015 push si

startCode1:2016 lea di, hallfameBuf[si]

startCode1:201A lea si, word_1E366[si]

startCode1:201E push ds

startCode1:201F pop es

startCode1:2020 mov cx, 10h

startCode1:2023 repne movsw

startCode1:2025 pop si

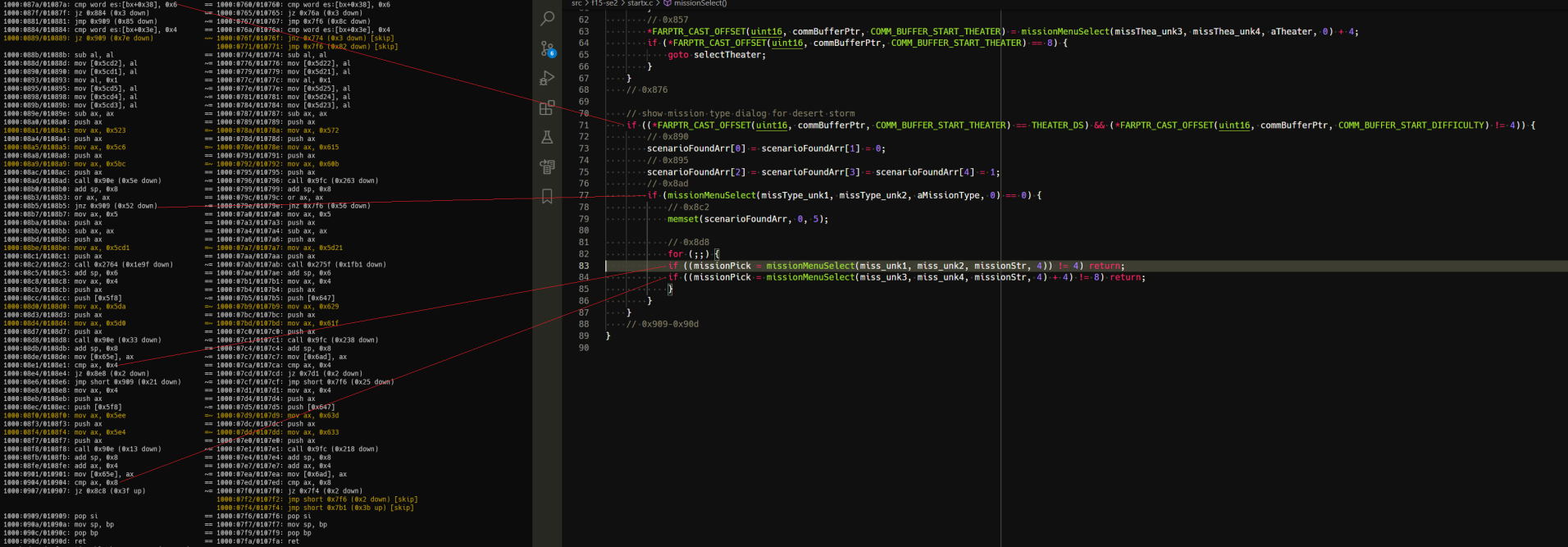

startCode1:2026 inc [bp+var_6]It uses the so-called string instruction repne movsw to copy 16 (10h) 2-byte words from one buffer to another, which is what would be known in C as a memcpy(). But the thing is, this compiler does not support inline functions, so I would be expecting a normal call to the C library instead. An another possibility is that this function was manually written in assembly. But it does not smell as such, I was able to get a large portion of it before this construct to match, it calls other functions from the C library, uses stack variables instead of registers…

An another thing is that technically repne movsw is an illegal instruction. The way it works, is there are two so called prefix opcodes for string instructions like MOVS/CMPS/SCAS/STOS in the 8086 instruction set which cause those instructions to be executed in a loop, as many times as the number in the CX register. The first one is 0xF2 and it represents REPNE/REPNZ, the other one is 0xF3 and it represents REP/REPE/REPZ. So, technically REP is the same thing as REPE or REPZ, while REPNE is the same as REPNZ. However, convention dictates that REP be paired with MOVS (memcpy()) and STOS (memset()), while REPE/REPZ/REPNE/REPNZ with CMPS (memcmp()/strcmp()) and SCAS (strlen()). The difference between REPE/REPZ and REPNE/REPNZ is that while both execute the string instruction CX-times, the former will terminate when the zero flag ZF becomes 1, while the latter will do so when the flag becomes zero. As CMPS or SCAS are proceeding down the “string”, they affect the flags based on the comparisons performed at individual locations, so this is a way to say “proceed until string end or until 0/not 0”. Because MOVS and STOS do not affect flags, it does not (technically) make sense to use REPNE on them - it should be REP MOVSW, but it works just as well. Whew. This was hard for me to distill, but I could not find a complete explanation online, so there you go.

So, has this been hand-crafted in assembly after all? Not necessarily, as MSC 5.1 is capable of emitting repne movsw. Whoa there, didn’t I say it does not support inline functions? Well yes I did, but let me introduce you to high tech from 1989: instrinsic functions!

What it does is, you build your code with /Oi, and the calls to the limited set of standard library functions will (hopefully) be replaced with inlined versions generated by the compiler. Let’s give it a go then, shall we?

#include <memory.h>

char a[] = "foobar";

char b[] = "barfoo";

int main() {

memcpy(b, a, 0x6);

return 0;

}ninja@dell:eaglestrike$ make hello cl /Gs /Oi /c /Foe:\hello.obj hello.c link /M /NOD /I hello.obj,e:\hello.exe,,slibce.lib;

This results in the following code:

00000012 B90600 mov cx,0x6

00000015 BF4800 mov di,0x48

00000018 BE4200 mov si,0x42

0000001B 8CD8 mov ax,ds

0000001D 8EC0 mov es,ax

0000001F D1E9 shr cx,1

00000021 F2A5 repne movsw

00000023 13C9 adc cx,cx

00000025 F2A4 repne movsbIt puts the number of bytes in CX (mov cx, 0x6), then divides it by 2 (shr cx, 1) to obtain the number of 16-bit words to transfer in bulk with repne movsw, and if the count was uneven, adc cx, cx/repne movsb will transfer the remainder. Here, the count is even, but as you can see it’s not smart enough to get rid of the adc thing. I’ve tried everything that I could think of, set different optimizations like /Oa (no aliasing present, pinky swear), changed the type of the arrays to int instead of char (memcpy() takes void * so it should not matter, but maybe the compiler checks it?), tried specifying explicit sizes for the arrays, used pointers instead - nothing worked.

What, you thought I had answers? Sorry, not this time. I have no idea how to make this match. The closest I’ve been able to get was to build with MSC 6.0 - it was smart enough to figure out it didn’t need adc/movsb any more. But it emitted rep movsw instead, so it’s still not a match, and ultimately useless. There are nop instructions before and after this routine, which might mean it comes from a separate C source file of its own, and was built with a different compiler and different flags than the rest of the code, but I don’t know what those might be, and I’m not eager to relive the Great Hunt at this time. What I ended up doing was to ignore this routine and move on – for now. I might get a bathroom epiphany, or I will end up rewriting it into non-identical code at the end. 80% is a long way to go, so I’m not going to waste it getting hung up on this.

Till next time then.