Hunting for the Right Compiler, Part 1

(This post is part of a series on the subject of my hobby project, which is recreating the C source code for the 1989 game F-15 Strike Eagle II by reverse engineering the original binaries.)

Back when I was having an initial look around the game, I was pretty excited to find a C runtime library copyright string embedded in the game’s executables:

ninja@dell:03_test$ xxd egame.exe

[...]

00022d70: 0000 0000 0000 0000 4d53 2052 756e 2d54 ........MS Run-T

00022d80: 696d 6520 4c69 6272 6172 7920 2d20 436f ime Library - Co

00022d90: 7079 7269 6768 7420 2863 2920 3139 3838 pyright (c) 1988

00022da0: 2c20 4d69 6372 6f73 6f66 7420 436f 7270 , Microsoft Corp

The 1988 date tells me that this executable was linked with the version of the library that shipped with the Microsoft C 5.1 compiler. Knowing the compiler is important, because it opens the possibility of the reconstruction being demonstrably perfectly accurate - if I reconstruct the C code correctly, and build it with the correct compiler using the correct options, I should obtain a binary that is identical to the original. If the game had been written in pure assembly (and hence it’s impossible to write C code that results in the same instructions), or if I can’t get my code to match the original binary for some other reason, there is always the possibility that my reconstruction contains mistakes, resulting in inaccurate behaviour of the game. So, it was understandable that discovering the compiler made me excited.

So it’s finally time to get started on the reconstruction. I have obtained a copy of MS C 5.1 and studied its user guide. The workflow I came up with is as follows:

- Look at the original game’s instructions in IDA, starting from the

main()function. - Figure out what they do and write the equivalent C code in an editor.

- Compile the reconstructed code with the MS C 5.1 compiler under DOS

- Disassemble the compiled binary and compare the instructions to the original ones

- If the instructions don’t match, go back to #2 and tweak the code

- If the instructions do match, give myself a pat on the back and move onto the next instructions in #1

The process is repeated for all the functions in the binary until everything is covered and matching. The code does not need to be very pretty or even understandable at this point - getting too deep into the details and trying to figure out too much about the actual intent of the code is adding more complexity to an already difficult task. Research and clarification will be easier later when the code is complete and can be instrumented with logging or run under a symbollic debugger. It’s a matter of preference, but I think dummy function and variable names (e.g. unknown_123) are fine at this stage. Of course, if something is pretty evident even at this stage, I go ahead and name it properly (e.g. timerInterruptRoutine). No point in discovering the same thing twice.

Besides the main challenge of doing the reconstruction, there are two technical problems with this process.

First, I don’t want to have to edit the code in DOS. If possible, I don’t want to go into DOS to run the compiler either, the build should be as streamlined as possible to enable quick iterations. Ideally, I want to be able to edit the code in my modern environment, run make at the command prompt and have the DOS compiler run inside an emulator silently. To that end, I have created a bash script which composes a DOS .BAT file that takes care of mounting the required paths, setting environment variables etc. before starting it with DosBox in headless mode, which means I don’t even get a DosBox window, it all just runs quietly to completion and terminates:

SDL_VIDEODRIVER=dummy dosbox -conf toolchain.conf $batfile -exit &> /dev/null

Then, I created a Makefile with recipes that run the script with appropriate arguments:

DOSBUILD := tools/dosbuild.sh

$(F15_SE2_BUILDDIR)/%.obj: $(F15_SE2_SRCDIR)/%.c $(F15_SE2_HDRS)

@$(DOSBUILD) cc $(C_TOOLCHAIN) -i $< -o $@ -f "$(CFLAGS)"

$(F15_SE2_BUILDDIR)/%.obj: $(F15_SE2_SRCDIR)/%.asm

@$(DOSBUILD) as $(ASM_TOOLCHAIN) -i $< -o $@ -f "$(ASFLAGS)"

$(F15_SE2_BUILDDIR)/%.exe:

@$(DOSBUILD) link $(LINK_TOOLCHAIN) -i $^ -o $@ -f "$(LINKFLAGS)" Now I can just do this:

ninja@dell:eaglestrike$ make build-f15-se2/start.exe

--- build running cl from msc510

cl /Gs /Os /Id:\f15-se2 /DMSC_VER=5 /c /Foe:\start.obj f15-se2\start.c

--- build running masm from masm510

masm /t f15-se2\slot.asm,e:\slot.obj,,;

--- build running link from msc510

link /M /NOD start.obj slot.obj,d:\start.exe,,slibce.lib;

Excellent, now onto the second, more difficult problem. Comparing whether the instructions match manually is going to be a huge pain. I could disassemble the original and the partially reconstructed binary into textfiles and run a diff tool on the results, but it’s going to show a lot of differences because, especially initially, the layout of the two files is going to be different, and the code/data addresses referenced by the instructions are going to be different, even if the code is correct, resulting in a lot of visual “chaff” that will distract from the actual meaningful differences that I want to see at first glance.

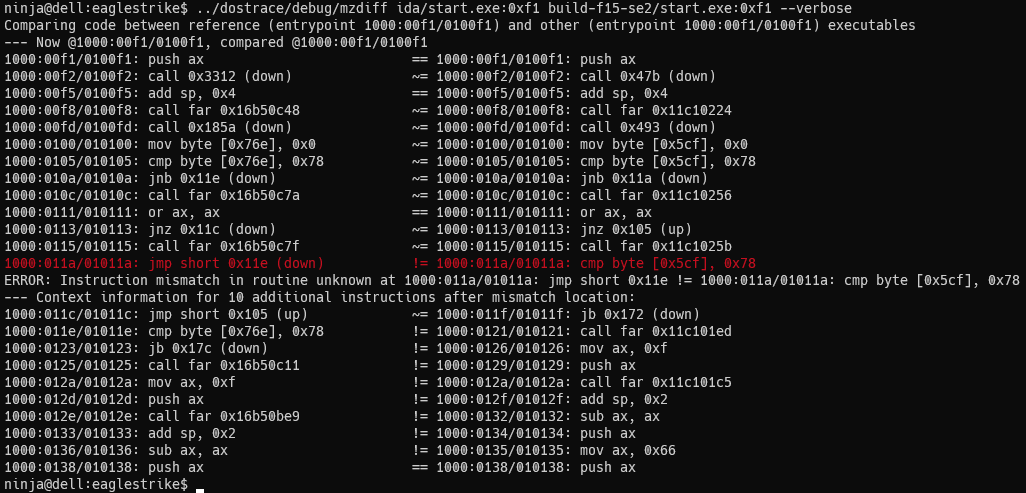

This second problem actually took me almost two months to (mostly) solve to my satisfaction. I implemented the mzdiff tool in mzretools which lets me specify the compared binaries, as well as the start locations in both I wish to compare at, and possibly some options on how strict the comparison should be. The tool decodes 8086 instructions and compares them, but not blindly byte by byte. When it sees an address operand that differs between the two, it will look it up in an address translation map between the two executables and see if the difference is consistent. If there is no translation, a new one will be recorded and kept for future reference. Here is a sample output:

The tool shows the instructions of the reference executable on the left, the compared executable on the right, and it displays == for ones that match perfectly, ~= and =~ for ones that differed in the first or second operand respectively, and of course != for a mismatch, which is also helpfully highlighted in red.

Actually, let me also explain about my expectations as to obtaining an “identical” executable. I do not care if the binary is byte-for-byte binarily identical. It might be nice to achieve as a sort of cherry on top once the code is nice, but for now I do not also care about whether the data segment layout matches the original exactly, same for the functions. I only want all the code and data to be there, and be doing the same thing. I think focusing on 100% accuracy is detrimental to making progress, and the tool lets me focus on the instructions and hides everything else. It means there is a slight chance I can still make mistakes, but I’m willing to live with that, and happily leave sorting it out for later. Divide and conquer, and never bite off more than I can chew.

Anyway, thus armed, I can actually start working on the game using the described workflow. Let’s look at the game’s opcodes from the top of main() in START.EXE:

00000010 55 push bp

00000011 8BEC mov bp,sp

00000013 83EC1C sub sp,byte +0x1c

00000016 56 push si

00000017 C7068C620000 mov word [0x628c],0x0

0000001D C7068A62F204 mov word [0x628a],0x4f2

00000023 C706FC450000 mov word [0x45fc],0x0

00000029 C706FA45F404 mov word [0x45fa],0x4f4

0000002F C746F00000 mov word [bp-0x10],0x0

00000034 C746EEF004 mov word [bp-0x12],0x4f0

00000039 C45EEE les bx,[bp-0x12]

0000003C 268B07 mov ax,[es:bx]

0000003F A3F477 mov [0x77f4],ax

00000042 C706F2770000 mov word [0x77f2],0x0

00000048 268B07 mov ax,[es:bx]

0000004B A30646 mov [0x4606],ax

0000004E C70604460E12 mov word [0x4604],0x120e

[...]La di da di da, clickety clickety…

// to easily disable DOS-specific keywords when I build it on a modern system some day

#define NEAR near

#define FAR far

union FarAddress {

struct { uint16 off, seg; } data;

uint8 FAR *ptr;

};

#define FARPTR_CAST(type, addr) ((type FAR*)addr.ptr)

static union FarAddress needSplash;

static union FarAddress iacaSuFlag0Ptr;

static union FarAddress commAddr;

static union FarAddress commBufferPtr;

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

union FarAddress iacaPtr;

needSplash.data.seg = SEG_LOWMEM;

needSplash.data.off = OFF_IACA_NEEDSPLASH;

iacaSuFlag0Ptr.data.seg = SEG_LOWMEM;

iacaSuFlag0Ptr.data.off = OFF_IACA_FLAG2;

iacaPtr.data.seg = SEG_LOWMEM;

iacaPtr.data.off = OFF_IACA_START;

commAddr.data.seg = *FARPTR_CAST(uint16, iacaPtr);

commAddr.data.off = 0;

commBufferPtr.data.seg = *FARPTR_CAST(uint16, iacaPtr);

commBufferPtr.data.off = COMM_STARTBUFFER_OFFSET;

// more to come later...

return 0;

}Compile, compare, match. Well, it didn’t right away, but I kept at it and got it to match. This went on for a little while and I was starting to feel confident. Then I came across this bit of code:

0100 mov timerCounter, 0

0105 waitForKey:

0105 cmp timerCounter, 78h ; this is increased in a timer IRQ service routine elsewhere

010A jnb short keyOrTimeout ; timeout of 78h (120 ticks) exceeded, break out of loop

010C call far ptr check_keybuf ; check for keypress

0111 or ax, ax ; check for zero return value (faster than cmp reg,imm)

0113 jnz short continue ; ax != 0: no keypress, continue spinning

0115 call far ptr getkey ; else: fetch key

011A jmp short keyOrTimeout ; ...and break out of loop

011C continue:

011C jmp short waitForKey ; try again

011E keyOrTimeout:

011E cmp timerCounter, 78h ; out of the loop, check reason (timeout or not)This does not look too complicated. This happens after the first splash screen containing the Microprose logo is displayed. A simple loop to spin around waiting until a timeout is exceed or a key is pressed, and depending on the result it will later display the rest of the intro (if no key was pressed), or skip straight to the game. It’s nothing to a seasoned reversing pro like me!

La di da, clickety clickety…

static char volatile timerCounter;

for (timerCounter = 0; timerCounter < 0x78;) {

if (check_keybuf() == 0) {

getkey();

break;

}

else continue; // superfluous, but reflects the original instructions

}

if (timerCounter >= timeout) {

// continue displaying intro...

} Compile, compare… Whoopsy!

1000:0100/010100: mov byte [0x76e], 0x0 ~= 1000:0100/010100: mov byte [0x5cf], 0x0 1000:0105/010105: cmp byte [0x76e], 0x78 ~= 1000:0105/010105: cmp byte [0x5cf], 0x78 1000:010a/01010a: jnb 0x11e (down) ~= 1000:010a/01010a: jnb 0x11a (down) 1000:010c/01010c: call far 0x16b50c7a ~= 1000:010c/01010c: call far 0x11c10256 1000:0111/010111: or ax, ax == 1000:0111/010111: or ax, ax 1000:0113/010113: jnz 0x11c (down) ~= 1000:0113/010113: jnz 0x105 (up) 1000:0115/010115: call far 0x16b50c7f ~= 1000:0115/010115: call far 0x11c1025b1000:011a/01011a: jmp short 0x11e (down) != 1000:011a/01011a: cmp byte [0x5cf], 0x78 ERROR: Instruction mismatch in routine main at 1000:011a/01011a: jmp short 0x11e != 1000:011a/01011a: cmp byte [0x5cf], 0x78 --- Context information for 10 additional instructions after mismatch location: 1000:011c/01011c: jmp short 0x105 (up) ~= 1000:011f/01011f: jb 0x172 (down) 1000:011e/01011e: cmp byte [0x76e], 0x78 != 1000:0121/010121: call far 0x11c101ed

The compiler eliminates the superfluous intermediate jump to 0x11c which jumps back up to 0x105 to continue with the next iteration of the loop and just jumps directly to 0x105 because that’s more efficient. The end result is the same. But the comparison is off and I was aiming for perfection! Worse still, it throws off my tool that I spent two months creating and I’ll be damned before I give up and revert to manual diffing. 😉

I will spare the reader the details of the number of equivalent variants of this loop that I developed. No matter what I try, pretty much an identical sequence of instructions is emitted that does not match the original. In short, none of the following worked, the compiler is too smart:

- adding explicit continue in an else clause in the loop - eliminated

- adding empty instructions in the else clause (

;,(void*)NULL) - eliminated - placing explicit intermediate

goto-s in the loop code to force the intermediate jump - eliminated - rewriting the entire loop into

goto-based spaghetti code - reduced to identical optimal instructions

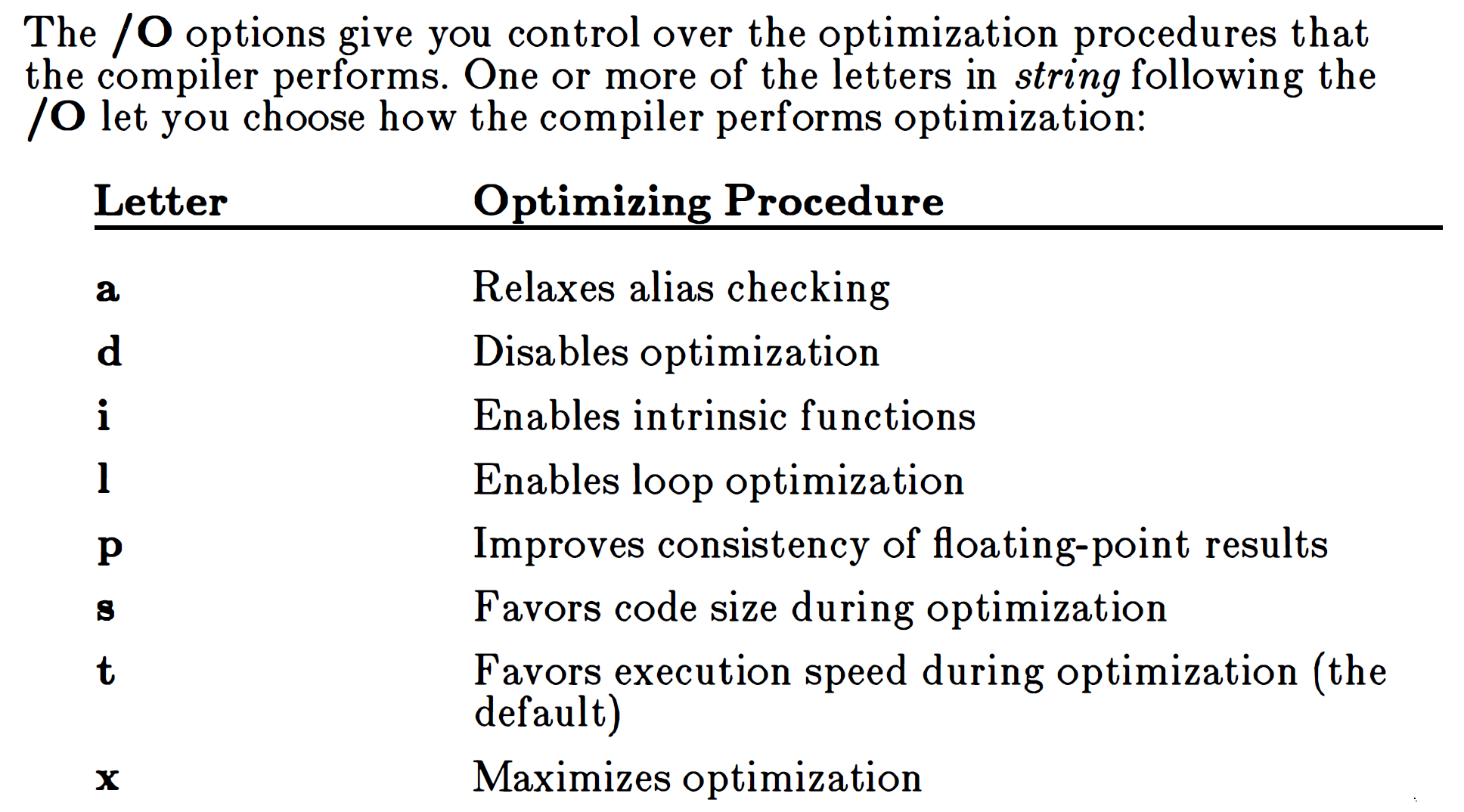

Wait, the compiler has some optimization options. Surely tweaking them will get me what I want? Let’s consult the fine manual:

Until now, I’ve been compiling without any options, which is equivalent to /Ot - optimize for speed. So I try all of the other options. Actually, I ended up writing a brute force Python script to generate all the combinations of these options (ones that made sense, because some are mutually exclusive) and ran my build + comparison for each combination - and for each variant of the loop C code that I could think of. I thought that was pretty smart of me, but the compiler was smarter. In short, /Od makes the loops unoptimized far too much, they have a bunch of additional jumps, but they are the wrong jumps, and everything everywhere else broke anyway. Other than that, all of the other options don’t seem to make a difference in the way the loop is compiled.

The compiler supports a #pragma loop_opt(on|off) which can be placed before a function and tells it that all loops inside that function should be optimized (or not). It should amount to a more fine-grained /Ol which I tried already, but perhaps it makes a difference? No, of course it doesn’t. Somebody please help?

An another possibility is that the code for this loop was not actually written in C but inline assembly. But MS C 5.1 does not support inline assembly.

Well, maybe it was written as a separate inline function in assembly, then linked and placed inline that way? Again, MS C 5.1 does not support inline functions. It supports something it calls “intrinsic functions” (enabled with /Oi) which are pretty much inline functions, but it only applies to a pre-determined subset of functions (memset(), strcpy(), inp(), some math functions…) from the standard library - you can either elect to have them expanded inline for performance, or keep them as regular functions. To my knowledge, there is no way to make an arbitrary function “intrinsic”.

Damnit. It’s not the right compiler. This one is too good at optimizing. We need a worse one. Or at least one which lets me control the optimizations more finely - which I guess would mean it’s actually better? No, no philosophizing! Bad kitty! 😉

Well, maybe they used an older version of MS C? I can’t fathom why, since they obviously have the library from MS C 5.1, so they also have the compiler available. But maybe this was compiled by a different developer than the one that linked it together at the end, and they had an older version on their PC? Well, no point in guessing, the only way to know for sure is to try. I extended my build script and the Makefile to support using different toolchains and abstract the differences between them so I can try multiple toolchain and flag combinations easily and quickly. The Python bruteforcing script again gets its fair share of use.

Trying MS C 5.0 required me to get rid of the fancy, “modern” (for 1988) // comments in favour of the /* ... */ ones. For all the work that took, it treated the loop exactly the same as 5.1.

Using MS C 4.0 was more challenging still - no argument names in function prototypes supported, function arguments and variables had to be declared in the ancient, pre-ANSI K&R style, before the initial brace. I had to introduce some #ifdefs all over to get the code to compile. It supports less optimization options (/Otsad), but it still behaves the same in regard to the loop code.

Using MS C 3.0 was like a gradual descent into hell - more keywords were unsupported, pragmas were not supported, nowadays-standard header files like STDDEF.H were missing from the C library. But it still didn’t give me what I wanted.

Older versions of the MS C compiler are barely functional, and this doesn’t seem like a reasonable path anymore. But there was another DOS compiler vendor in those days, a towering giant whose influence over the software development industry went far and wide. This is where the title of this post comes from:

Borland was selling a C compiler called Turbo C in the mid-to-late 80s. It boasted faster compilation times than the competition (hence the Turbo moniker), supported fancy features like inline assembly, and advertised its MS C interoperability. In 1990, when they released Turbo C++, the C compiler was folded into that and the standalone Turbo C discontinued. Then in 1991, Borland C++ was released which was aimed at the professional market, while the idea was for Turbo C++ to keep catering to the needs of hobbyists.

I know that the game has a MSC copyright notice inside, but I guess it’s possible the C code was compiled with Borland by one developer who had it installed on their PC, and then somebody else made some tweaks in the assembly code (the executable contains some functions that are clearly manually coded in assembly in another code segment) and linked the object files with the MS C library for release. Computers were slow back then and compiling took time. Why bother recompiling the source code, or maybe the person doing the linking didn’t even have the source code, just the object files? There are many possible things that could have happened.

The game’s 1989 release date means that the following Borland compilers are on the table:

- Turbo C 1.0 (1987)

- Turbo C 1.5 (1988)

- Turbo C 2.0 (1988)

- Turbo C 2.01 (1989, stretching it)

…but the story of that investigation is going to have to wait for Part 2.