Having a first look around F-15 SE2

(This post is part of a series on the subject of my hobby project, which is recreating the C source code for the 1989 game F-15 Strike Eagle II by reverse engineering the original binaries.)

So, let’s see what we’re up against, shall we?

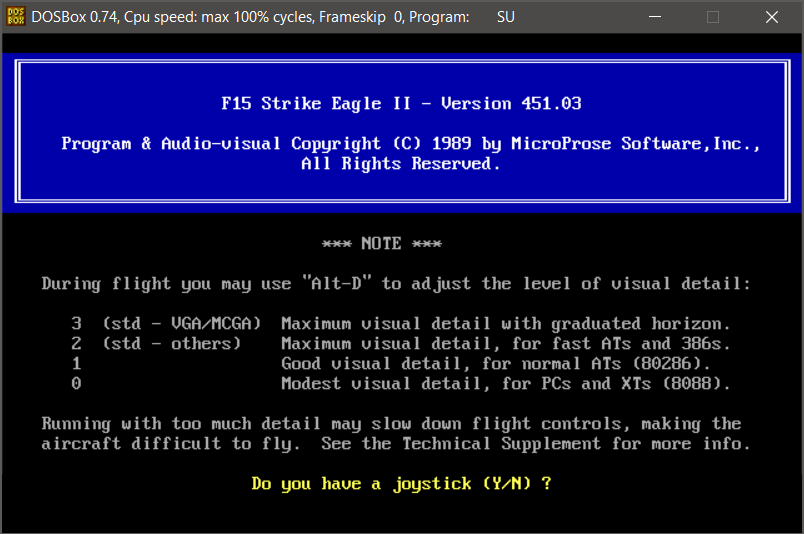

The game has two widely available versions: 451.01 and 451.03 - these numbers are advertised when launching the game, when the user is asked for their machine’s video and sound capabilities.

- version 451.01 is the original release

- version 451.03 is the extended version containing the additional Desert Storm scenario, and it also has some differences like nighttime missions being present (basically the colors of the sky gradients change)

ninja@dell:bin$ du -sh 451.01 451.03

756K 451.01

1.5M 451.03

There could have been other versions, especially development ones, but I’m not aware of their existence. For this project, I’m going to focus on the extended version. As can be seen above, the total size of the game is 1,5 megabytes. These are the game files:

ninja@dell:451.03$ ls

1.pic adv.pic cockpit.pic f15.com isound.exe lb.3dt medal.pic nsound.exe right.pic vn.3dg

15flt.3d3 armpiece.pic dbicons.spr f15.spr jp.3d3 left.pic mgraphic.dem persian.spr rsound.exe vn.3dt

2.pic asound.exe death.pic f15dgtl.bin jp.3dg libya.spr mgraphic.exe pg.3d3 start.exe vn.spr

256left.pic ce.3d3 demo.exe f15loadr jp.3dt libya.wld misc.exe pg.3dg su.exe vn.wld

256pit.pic ce.3dg desk.pic f15storm.exe jp.spr me.3d3 nc.3d3 pg.3dt tgraphic.exe wall.pic

256rear.pic ce.3dt ds.exe gulf.wld jp.wld me.3dg nc.3dg photo.3d3 title16.pic

256right.pic ce.wld egame.exe hallfame labs.pic me.3dt nc.3dt promo.pic title640.pic

3.pic ceurope.spr egraphic.exe hiscore.pic lb.3d3 me.spr nc.wld read.me tsound.exe

4.pic cgraphic.exe end.exe install.exe lb.3dg me.wld ncape.spr rear.pic vn.3d3

At first glance, several categories of files can be recognized:

- the single COM file is the main executable of the game

- multiple secondary EXE executable files

- PIC files for (mostly) stationary graphics, including the pilot roster, mission briefing, etc. but also the cockpit graphics. These seem to be encoded with some form of RLE, perhaps LZW encoding, but I’ve not cracked the encoding yet

- 3D3, 3DG and 3DT files for each of the game scenarios (CE: Central Europe, LB: Libya, ME: Middle East, PG: Persian Gulf, JP: ?). The format and exact purpose of these is also not yet determined, from some casual browsing in the game executables, it looks like 3DG is “grid” and 3DT is “terrain” data, perhaps 3D3 is some model vertex data?

- a couple outliers: SPR (sprites? dbicons seems to be the medal etc. icons in the pilot roster, but not sure how different they would be from PIC), BIN, F15LOADR - all to be discovered in the future

From the point of view of the initial reverse engineering process, the most interesting files are the executables (COM/EXE). Analyzing these will tell me how the game works, and the purpose and format of the other game files like the mission data. There are quite a few of those at first glance:

ninja@dell:451.03$ ls *.exe *.com

asound.exe demo.exe egame.exe end.exe f15storm.exe isound.exe misc.exe nsound.exe start.exe tgraphic.exe

cgraphic.exe ds.exe egraphic.exe f15.com install.exe mgraphic.exe ninja.exe rsound.exe su.exe tsound.exe

At the time of writing this, I have already 100% disassembled and understood the initial executable F15.COM. This file contains heavily obfuscated, self-modifying code that I think also contains copy protection (the game originally came on a floppy disk that I think contained some fuzzy bits), and discussing it will be a long story for another time. In fact, due to the way the obfuscation works, this game will not work in DosBox unless the 386_prefetch cpu type is enabled, I think because at some point it actually overwrites its own code as it’s running, which I think makes it go into the weeds until the emulator simulates a prefetch queue for the CPU. I was lucky that somebody (probably back in the 80s) made a deobfuscated and cracked version that has a simple layout that’s easy to disassemble and understand. This part I think was implemented in hand-crafted assembly code (and passed through some in-house obfuscator as mentioned), and is only 1550 bytes long when deobfuscated (~8K in obfuscated state). I already have a drop-in reconstruction written in C that works and provides some additional debugging output. In short, the logic implemented by F15.COM is as follows:

- Initialize some shared structures (will be described in detail later)

- Launch the SU.EXE (SetUp) executable, letting the user select their video and sound card and calibrate the joystick if present

- Load the drivers for the selected audio and video hardware plus the MISC driver

- Launch the main game loop

The main game loop consists of running the following executables in sequence - by looking at the title bar of DosBox, I can see which executable is currently running, and this was also confirmed by analyzing the code of F15.COM. If any of the executables exits with an unexpected error code, the main loop is interrupted and it exits to the DOS prompt with function 21.4c.

- DS.EXE /1

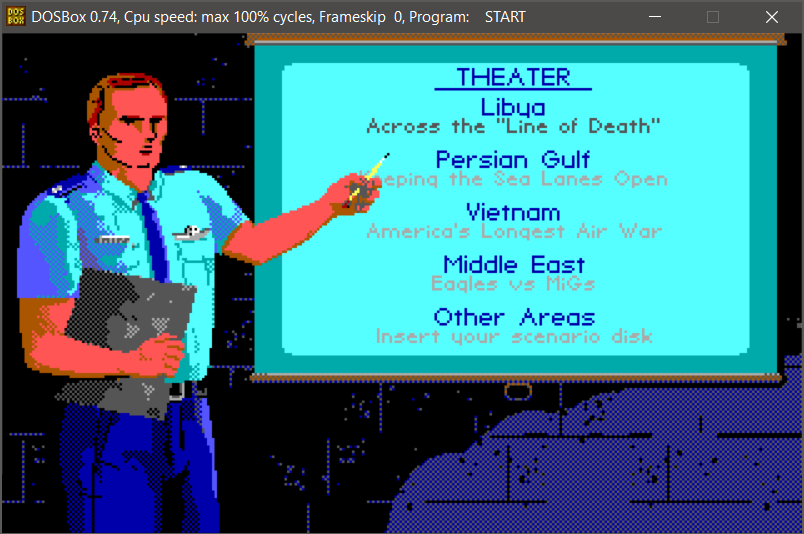

- START.EXE

- DS.EXE /2

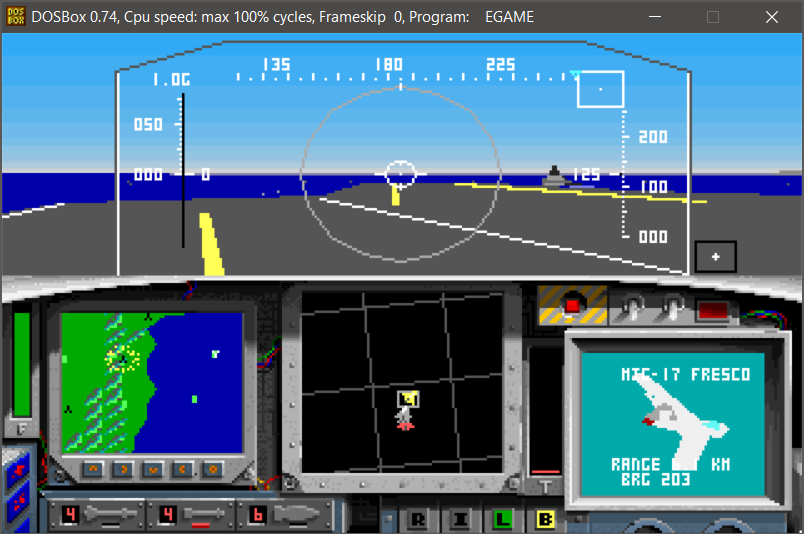

- EGAME.EXE

- DS.EXE /1 (bug?)

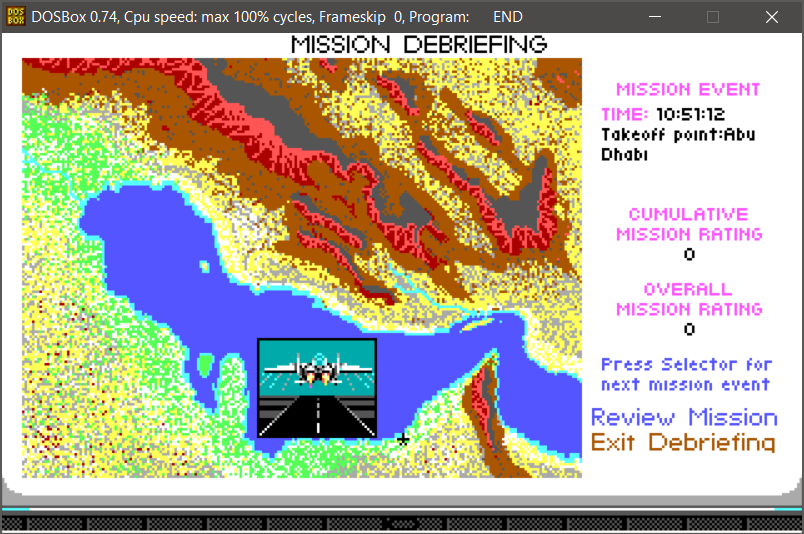

- END.EXE

- Go back to 1

This is a good segway into the purpose of the EXEs. Most of them crash/freeze if launched directly, as they need the initialization done in step 1) of F15.COM to work, and some are not actual runnable executables but overlays (more on that later).

SU.EXE: initial SetUp, asks the user (in text mode) for their machine configuration (and optionally lets them calibrate the joystick), or obtains that configuration from commandline switches. I have disassembled and analyzed most of it and it also sets some values in the configuration buffer that is shared between the other game executables, but because I’m not planning to implement inferior graphics or sound support, I figure it can mostly be ignored.

DS.EXE: I have also disassembled a part of it, and as far as I can see, its only purpose is to check if a needed executable exists - this is selected by the ‘/1’, ‘/2’ commandline switch, which is why I think there is a bug because the main game loop never checks for END.EXE but START.EXE when it’s about to launch END. If it’s missing, DS.EXE shows a prompt (in graphical mode) to insert a different floppy disk, hence the name (DiskSwap). I don’t think it contains any copy protection code, as it exits as soon as it determines that the file exists, so I think it’s okay to ignore completely in this project.

START.EXE: shows game credits on the first run, lets you pick a pilot and the mission, does a mission briefing, probably also loads the mission - need to disassemble, analyze and reimplement it for this project. I have some progress on it, but still far from done.

EGAME.EXE: the main part of the game, the actual 3d flight engine. Haven’t yet touched it yet other than a cursory look around inside. Thinking about all the 3D projection math that will have to be scraped from its disassembly at some point is giving me night terrors. :/

END.EXE: after the mission ends, it shows the debriefing, and optionally a static image if you crashed, got promoted or relegated to a desk job. Didn’t look at any of it yet, but will also need to reimplement for this project.

xGRAPHIC.EXE: these files are the overlay video driver files for the specific video adapters of the day (EGRAPHIC - EGA, CGRAPHIC - CGA). I will discuss the details of these overlays at a later time, but for this project I will be focusing on the most superior, 256 color MCGA graphics, so I need to analyze and reimplement MGRAPHIC.EXE and ignore the rest. I have some progress on that, but not yet completely done.

xSOUND.EXE: likewise, driver overlays but for sound. The best this game can do is Adlib sound, but because it’s mostly a static hiss for the engine sound, some sound effects and a gimmicky speech effect at key mission points, I will be ignoring sound completely, at least for now.

MISC.EXE: a tiny overlay file with some “misceallenous” functions, mostly for keyboard and joystick input. Will need to implement it, but it is really very simple.

The remaining executables are not relevant to the game; DEMO shows some static screens from other Microprose games, F15STORM.EXE likewise is a slideshow of the gameplay of this game, perhaps meant as a store demo mode.

So, bottom line is I will need to reverse engineer and reimplement the following files:

ninja@dell:451.03$ du -sh start.exe egame.exe end.exe mgraphic.exe misc.exe

24K start.exe

56K egame.exe

20K end.exe

12K mgraphic.exe

4.0K misc.exe

ninja@dell:451.03$ file start.exe egame.exe end.exe mgraphic.exe misc.exe

start.exe: MS-DOS executable, LZEXE v0.91 compressed

egame.exe: MS-DOS executable, LZEXE v0.91 compressed

end.exe: MS-DOS executable, LZEXE v0.91 compressed

mgraphic.exe: MS-DOS executable

misc.exe: MS-DOS executable

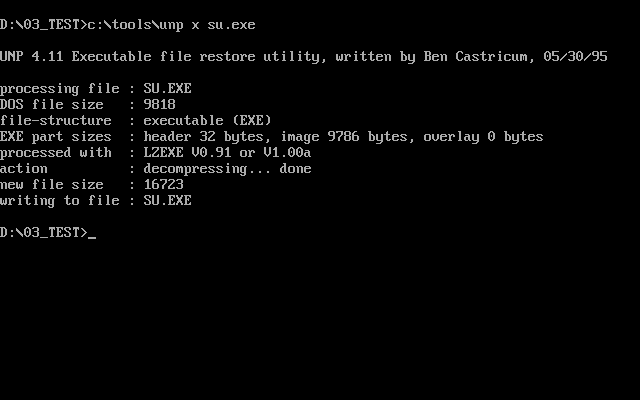

The files seem to be relatively small, but the three main ones are compressed. The compression can be undone with either UNLZEXE or UNP under DOS (in the 451.01 release, some of the files were compressed with EXEPACK), and they inflate to the following:

ninja@dell:03_test$ du -sh su.exe start.exe egame.exe end.exe

20K su.exe

48K start.exe

168K egame.exe

40K end.exe

Now for an important discovery. Looking inside any of the 3 main EXEs, the following string can be found in the data segment:

ninja@dell:03_test$ xxd egame.exe

[...]

00022d70: 0000 0000 0000 0000 4d53 2052 756e 2d54 ........MS Run-T

00022d80: 696d 6520 4c69 6272 6172 7920 2d20 436f ime Library - Co

00022d90: 7079 7269 6768 7420 2863 2920 3139 3838 pyright (c) 1988

00022da0: 2c20 4d69 6372 6f73 6f66 7420 436f 7270 , Microsoft Corp

Doing some googling, that signature belongs to the standard library for the C programming langage shipping with the Microsoft C Compiler version 5.0 or 5.1, which would line up with the game’s release year of 1989 (the compilers were released in 1987 and 1988 - seems Microprose was using cutting-edge tools!) . Being able to identify the compiler is good news for the following reasons:

- The game is implemented in a relatively high-level language that I’m familiar with, and creating the reconstruction will be easier than if it was all done in straight assembly. I can translate code from disassembly to C somewhat mindlessly, and then reason (and experiment) about what it’s trying to accomplish on the level of C rather than assembly.

- Some functions in the code will be possible to be identified by IDA as standard C library functions like

strcpy()orfopen(), limiting the amount of code that needs to be manually analyzed, and clarifying intent in other places that do. - More definite verification of the fidelity of the reconstruction will be possible - if the code generated from my C reconstruction generates the same opcodes as seen in the orginal game, then it means the reconstruction is correct.

- After the reconstruction is done, it will be easier to port it to a modern system, just need to wrap the direct memory accesses, the far pointer stuff, and rewrite the video driver calls to the MCGA graphics driver into SDL wrapper functions.

I was able to find a copy of MS C 5.1 online and installed it in dosbox. I obtained what are known as IDA FLIRT signatures from the library files that came with it, and importing them into IDA was successful - it was able to identify and mark some functions as belonging to the standard library - yay! I also found some scanned documentation for both the compiler and the library itself and reading through them has been enlightening in the way that DOS C programs were written, compiled, and debugged back in the day. I have also made myself some wrapper scripts for executing the compiler in the emulator from within a Makefile, so I can easily develop the reconstruction in a modern environment, and build it just by running make.

That’s enough for an introduction, I will be writing up my findings in more detail in subsequent posts.