Reassembling the disassembly

(This post is part of a series on the subject of my hobby project, which is recreating the C source code for the 1989 game F-15 Strike Eagle II by reverse engineering the original binaries.)

After the previous post where I had finally managed to figure out the compiler flags used back in 1991 to compile the game, which now let me generate 100% identical machine instructions from C code, I was in high spirits and managed to transcribe a fair amount of instructions into C. That was fun, but soon enough I was shaken out of my comfort zone by an innocent question: “have you tested your ported code with the original game?”

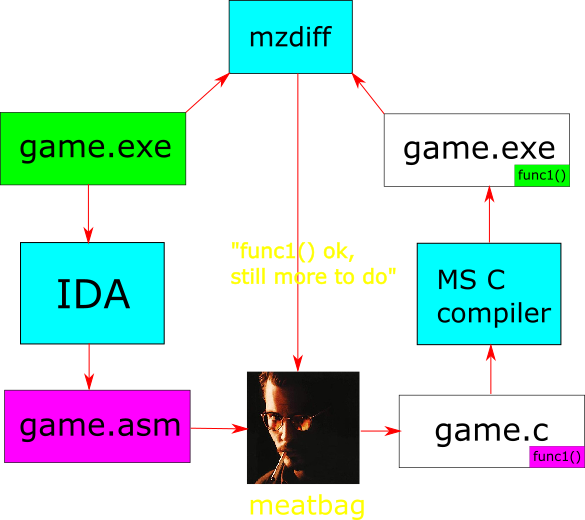

Thing is, I can’t easily do that. The (let’s say “additive”) approach I’ve followed until now, where I’m analyzing the output of IDA and reconstructing the C code function by function looks something like this:

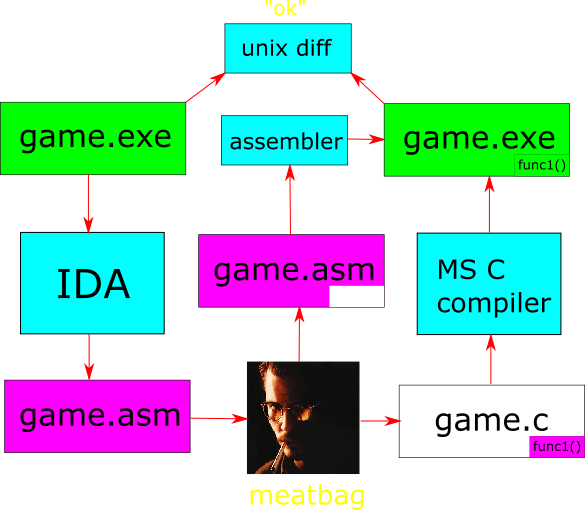

This has several downsides. For one, I don’t have a runnable version of the game until I’m done reconstructing all (or nearly all) of the functions. The other is that my recreation is not byte-for-byte identical with the original (again, at least not until I’m done rewriting the whole thing), which means I needed to make a special tool to compare instructions, so that I know if the reconstruction is correct or not. It’s been working pretty good so far, but having a runnable version which I can instrument with debug statements if necessary, would be a huge advantage. So far, I had not considered it because it seemed an insurmountable task, but can we actually achieve and maintain binary identity through the reconstruction? That would mean changing the approach to a “subtractive” one, where I take a function away from the perfect copy, reconstruct it in C, and put it back in:

The first step to achieve that would be to take the disassembly generated by IDA and try to reassemble it into an EXE file that is identical with the original. In theory, this should work because a dissasembly is essentially a listing of all the bytes in the file. But due to assembler syntax quirks, instruction encoding differences, segment layout, padding and alignment etc., the result is not guaranteed, which is why I have not tried to do it in earnest until now.

Jumping into the deep end, let’s try to just assemble the file that IDA spits out for the first game executable, START.EXE. The assembly syntax that it generates appears to be compatible with MASM, although I think there is also an option to switch it into TASM’s Ideal Mode, which as I understand is Borland’s attempt to enforce a strict style of assembly code that removes some ambiguities, and was preferred by some people back in the day. For now let’s go with the default syntax and try to assemble with MASM 5.10 under DOS. I’m using a shell script which does some weird stuff to launch the assembler inside Dosbox in headless mode, then examines the output, which is handy for use in Makefiles, no manual building from DOS necessary:

ninja@dell:eaglestrike$ tools/dosbuild.sh as masm510 -i src/f15-se2/startraw.asm -o build-f15-se2/startraw.obj

--- build running masm from masm510

masm f15-se2\startraw.asm,e:\startraw.obj,,;

Microsoft (R) Macro Assembler Version 5.10

Copyright (C) Microsoft Corp 1981, 1988. All rights reserved.

f15-se2\startraw.asm(218): error A2070: Illegal combination with segment alignment

f15-se2\startraw.asm(634): error A2070: Illegal combination with segment alignment

f15-se2\startraw.asm(1291): error A2038: Left operand must have segment

f15-se2\startraw.asm(1380): warning A4057: Illegal size for operand

f15-se2\startraw.asm(1437): error A2038: Left operand must have segment

f15-se2\startraw.asm(1451): error A2038: Left operand must have segment

f15-se2\startraw.asm(1465): error A2038: Left operand must have segment

f15-se2\startraw.asm(1479): error A2038: Left operand must have segment

f15-se2\startraw.asm(1493): error A2038: Left operand must have segment

f15-se2\startraw.asm(1503): error A2064: Near JMP/CALL to different CS

[...]

46262 + 316264 Bytes symbol space free

2 Warning Errors

181 Severe Errors

Whoa, that’s a lot of errors. Actually, assembling this with a period-accurate assembler might not be the best idea. For one, the raw assembly file is more than 25k lines long, and comes in at about 530KB. This might or might not fit into memory (remember, the conventional memory limit in DOS is 640K, with some always reserved by the OS, and the assembler will take some as well), and I’m not sure if MASM can take advantage of extended memory. Fortunately, there are modern MASM-compatible assemblers that can emit 16bit object code in the OMF format which is accepted by DOS linkers. I’ve decided to use UASM. I had some problems with it, namely the latest binary release, which was 2.56 as of the time I’m writing this did not run on my WSL Ubuntu environment due to a glibc version mismatch. I managed to build it from source by checking out the 2.55 tag in the github repo, changing the CC = clang-3.8 line in the Makefile to just clang because the oldest I could find in APT was version 8, and finally replacing -ansi with -Wno-error=implicit-function-declaration in extra_c_flags. Now, let’s try again:

ninja@dell:eaglestrike$ ../UASM/GccUnixR/uasm -0 -Zm src/f15-se2/startraw.asm UASM v2.55, Sep 23 2023, Masm-compatible assembler. Portions Copyright (c) 1992-2002 Sybase, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Source code is available under the Sybase Open Watcom Public License. src/f15-se2/startraw.asm(218) : Error A2169: General Failure

That does not look encouraging. However, looking at the assembly file where it fails, the offending line contains an align 4 directive. IDA generated those (with varying amounts) in multiple places where there is a nop instruction or null bytes in the middle of code, and sometimes even in the middle of data. I could change every single align into a nop or db 0 manually in IDA, but there were too many so I didn’t want to bother. I think there is an option to disable generation of aligns, but I could not find it, so it’s time to start tweaking IDAs output.

I could substitute all occurences of align in an editor easily enough, but I decided to write a script to do it. This has the advantage of being able to quickly regenerate the tweaked disassembly after IDAs database of the code is updated, and also the script can probably be reused for other game executables in the future, for more work upfront, so it’s worth it in my book. Also, the script’s original version used the assembly file generated by IDA as its input, but I later switched to the IDA listing (.lst) file instead, which has segment and offset information on every line, so it’s easy to locate specific locations in the code, and I’m planning to use the script to surgically cut out routines that are going to be rewritten in C.

In order to keep this brief, here is what the script needed to do in order for the assembly to be accepted by UASM:

- Replaced all ocurrences of

align 2by anop, andalign 4by 2xnop. - Replace the far jump placeholders that are used as trampolines into the overlay driver functions, and which IDA renders as

jmp far ptr 0:0with literal bytes:db 0EAhfor the far jump opcode anddd 0for the far jump location placeholder value. - Replace all ocurrences of the invalid

repne movswinstruction with literal bytes as well:dw 0A5F2h(little endian). Technically, themovswinstruction only accepts therepprefix and UASM will not acceptrepne, but it seems to work fine when run on an actual CPU, so the literal bytes force the erroneous instruction.

At this point the generated code was successfully assembled into an .OBJ file and accepted by the MS C 5.1 linker, resulting in an EXE file. It is a couple kilobytes bigger than the original, so let’s look inside. I’ve generated a disassembly of the original and the reassembled executable with ndisasm, and used WinMerge to visually compare the listings. Initially, literally all offset values referencing data were off by a small amount, which resulted in a lot of visual clutter. That was solved by hexdumping the contents of the data segment of the original and the reconstruction, and comparing them in WinMerge again. Some data locations which had align directives were replaced by the script with nops, but were actually null bytes. There were only a few, so I changed them manually to dbs in IDA and reran the script (good thing I don’t have to redo it manually). That turned out much better, but there are still differences in the disassembly:

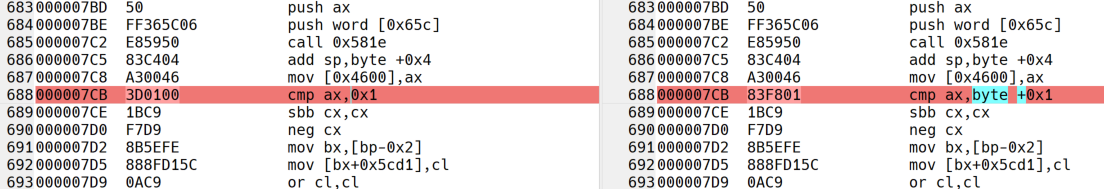

The encoding of some arithmetic instructions involving the AX register (add/sub/and/cmp ax, <immediate>) differs betweeen the original and what UASM generated. Don’t know if there’s a way to force the encoding needed with special syntax, so this was solved again by changing the instructions into literal byte seqeuces such as db 3Dh, dw <immediate> ; cmp ax, <immediate>. The same solution was used for a single instance of an or di, 2.

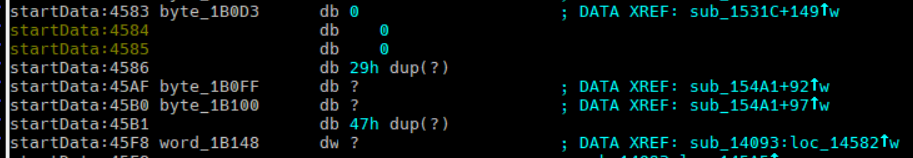

At this point, all code matched perfectly, but the contents of the data segment were still off, namely there was an extra bunch of zeros in the reconstruction that was not present in the original. Looking at the specific location where the zeros start, turns out this is where the uninitialized values db/dw/dd ? start:

This is the BSS section of data, uninitialized values which do not need to be placed in the executable, so in order to save space, the C runtime will just allocate space for this section and fill it with zeros when the program is run. I resized the data segment in IDA, terminating it at the location of the last initialized value, then created a new segment of class BSS where the uninitialized data starts:

startData segment byte public 'DATA'

; [...]

byte_1B0D3 db 0

db 0

db 0

startData ends

startBss segment byte public 'BSS'

db 29h dup(?)

byte_1B0FF db ?

byte_1B100 db ?

db 47h dup(?)

; [...]

startBss endsThis resulted in a lot of errors from UASM about being unable to reach values in the startBss segment, because it didn’t know which register (if any) holds a reference to it. This is normally solved by an assume directive, and IDA generated a lot of those all over the code. I decided to use the segment grouping feature of the assembler to put the data and bss segment into a common group, then telling it to assume the address of the group as a whole would be in the DS register:

.8086

.MODEL SMALL

DGROUP GROUP startData,startBss

ASSUME DS:DGROUPThe IDA-generated assumes were interfering with this, so I disabled them in the options. However, for some reason IDA also changed all references to the data segment with the newly-created BSS segment everywhere, leading to multiple “symbol not defined” from UASM. I didn’t want to fiddle with IDA too much, so I just ended up making the script terminate the data segment at the specific offset that is needed, and open a BSS segment there. The script really gives me endless possibilities.

At this point, the executable assembled and was 100% identical to the original. Yay! However, after copying the executable into the game folder, it ran up to the intro screen and froze. WTF? The executable is identical, so why doesn’t it work?

Up till now, I’ve been comparing the contents of the EXEs so called load module, that is the part that gets placed in memory by the DOS loader in order to run. The executable on disk also has a header, so let’s use mzhdr from mzretools to take a look at both headers and compare:

ninja@dell:eaglestrike$ ../mzretools/debug/mzhdr ida/start.exe

--- ida/start.exe MZ header (28 bytes)

[0x0] signature = 0x5a4d ('MZ')

[0x2] last_page_size = 0x146 (326 bytes)

[0x4] pages_in_file = 90 (46080 bytes)

[0x6] num_relocs = 148

[0x8] header_paragraphs = 39 (624 bytes)

[0xa] min_extra_paragraphs = 1078 (17248 bytes)

[0xc] max_extra_paragraphs = 65535

[0xe] ss:sp = e66:800

[0x12] checksum = 0x0

[0x16] cs:ip = 0:5542

[0x18] reloc_table_offset = 0x1c

[0x1a] overlay_number = 0

--- relocations:

[0]: 9:0, linear: 0x90, file offset: 0x300, file value = 0x6b5

[1]: a:6, linear: 0xa6, file offset: 0x316, file value = 0x6b5

[2]: a:f, linear: 0xaf, file offset: 0x31f, file value = 0x6b5

[3]: e:6, linear: 0xe6, file offset: 0x356, file value = 0x6b5

[4]: f:b, linear: 0xfb, file offset: 0x36b, file value = 0x6b5

[5]: 10:f, linear: 0x10f, file offset: 0x37f, file value = 0x6b5

[6]: 11:8, linear: 0x118, file offset: 0x388, file value = 0x6b5

[...]

[123]: 2e2:9, linear: 0x2e29, file offset: 0x3099, file value = 0x6b5

[124]: 2fb:e, linear: 0x2fbe, file offset: 0x322e, file value = 0x0

[125]: 2fe:f, linear: 0x2fef, file offset: 0x325f, file value = 0x6b5

[...]

In addition to the fixed-size initial fields, which were identical, the header also contains the relocation table, which is a list of locations in the executable which reference the segment value that the program is loaded into. Since that value is dependend on the amount of free memory, and can be different any time the executable is run, the DOS EXE loader needs to patch all of these with the actual correct value before running the program. For each relocation, the tool shows its address within the load module, the equivalent linear address, and what offset that corresponds to in the executable file (which would be the linear address plus the length of the MZ header), as well as the value that that location currently has (when patched, the actual load segment would be added to that value). The 0x6b5 value represents the data segment, but the executables differ by a single relocation entry numbered 124, referencing 0x0, aka the code segment. The tool sorts the table entries by the linear address, so it’s easy to see the differences when looking at the headers’ dumps alongside each other in WinMerge.

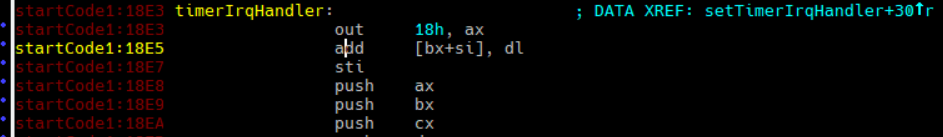

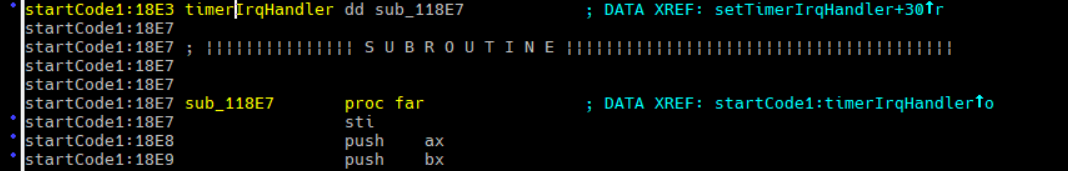

Looking at location 0x2fbe in IDA, I find this code:

The two leading instructions don’t seem to make much sense, but the sti fits perfectly in a interrupt handling routine. I undefined the 2 nonsense instructions and noticed that the bytes that make them actually spell the offset of the sti instruction below. Turns out the handler actually begins on the sti, and the 4 bytes before are just the far address to that handler:

Fixing that last bit makes all the relocations in the MZ header of the reconstruction match the original, and finally the reconstructed exe file runs perfectly inside the game. It’s still not perfect because the MZ header is padded with zeros to 1024 bytes in the reconstruction, while the original clocks in at 624 bytes, but I figured it’s of no consequence right now, and can always be addressed later if it keeps bothering me. In any case, achieving this is a significant step forward, but I still need to check whether the binary identity will hold once I start linking in C code.

An another problem is that now my executable comes with the MS C runtime library baked in, and I will need to do more investigation to figure out where it starts and ends inside the disassembly so I can remove its code and particularly the data, before I can link the code with the C library again. But both of these will be handled and written up another time.