Hunting for the Right Compiler, Part 3

(…continued from Part 2)

“(…) But there it was, just as the books said. You went in a circle, gave yourself endless trouble under the delusion that you were accomplishing something, and all the time you were simply describing some great silly arc that would turn back to where it had its beginning, like the riddling year itself.” – Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain

After writing up the previous part of the story of the futile compiler chase, I was pretty burned out. I had tried every compiler and option that could have conceivably been used by whoever modified the code of F15 SE2 for the 1991 scenario disk update before producing the final build and turning it over to manufacturing, yet that search turned out fruitless. The opcodes smelled of MSC 5.1. But it could not be forced to emit the specific sequence of jmp short instructions that was present in the original. Borland compilers could, but they produced differences elsewhere that likewise could not be made to go away. A classic catch-22.

I wanted to make progress on the reconstruction so I gave up on trying to make it perfect. I implemented options in the tool that I use for comparing my reconstruction with the original, which let it skip a number of differing instructions in both executables and moved on. I was not very happy about it, but I was able to finish main() and move on to other functions that way. I kept using MSC 5.1 because it seemed to produce the best matching code overall. Things seemed to be moving along until one day distaster struck. The next function to rewrite from assembly to C was supposed to be this one:

waitMdaCgaStatus proc near

iter_count = word ptr 4

push bp

mov bp, sp

loop_begin:

mov ax, [bp+iter_count] 🟢 check a loop counter

dec [bp+iter_count]

or ax, ax

jz short done 🟢 counter is zero, we're done

les bx, commAddr

cmp word ptr es:[bx+COMM_SETUP_MONOCHROME_OFFSET], 0 🟢 check a flag in the config

jz short cgaStatusZero ; 3da: CGA status register

mdaStatusZero:

mov ax, 3BAh ; port 3ba: MDA status register

push ax

call _inp

add sp, 2

test al, 80h

jnz short mdaStatusNonZero 🟢 repeat until MDA status bit is 1

jmp short mdaStatusZero ; port 3ba: MDA status register

mdaStatusNonZero:

mov ax, 3BAh

push ax

call _inp

add sp, 2

test al, 80h

jz short tryAgain 🟢 repeat until bit is 0

jmp short mdaStatusNonZero

tryAgain:

jmp short loop_continue

cgaStatusZero:

mov ax, 3DAh ; 3da: CGA status register

push ax

call _inp

add sp, 2

test al, 8

jnz short cgaStatusNonZero 🟢 repeat until CGA status bit is 1

jmp short cgaStatusZero ; 3da: CGA status register

cgaStatusNonZero:

mov ax, 3DAh

push ax

call _inp

add sp, 2

test al, 8

jz short loop_continue 🟢 repeat until MDA status bit is 0

jmp short cgaStatusNonZero

loop_continue:

jmp short loop_begin 🟢 next loop iteration

done:

mov sp, bp

pop bp

retn

waitMdaCgaStatus endpThis appears to be spinning in a loop, polling a bit from either the MDA or the CGA status register until it switches from 1 to 0. I think there may be a bug in there, but for now let’s just try to write a C equivalent. I can already smell trouble. Whenever I see a jmp short, especially around a loop, I get a nervous sweat.

void waitMdaCgaStatus(int16 iter)

{

while (iter-- != 0) {

if (*FARPTR_CAST_OFFSET(int16, commAddr, COMM_SETUP_MONOCHROME_OFFSET) != 0) {

while ((inp(PORT_MDA_STATUS) & MDA_STATUS_RETRACE) == 0) {}

while ((inp(PORT_MDA_STATUS) & MDA_STATUS_RETRACE) != 0) {}

}

else {

while ((inp(PORT_CGA_STATUS) & CGA_STATUS_RETRACE) == 0) {}

while ((inp(PORT_CGA_STATUS) & CGA_STATUS_RETRACE) != 0) {}

}

}

}Compile, link, compare. Well of course it does not match.

000004EC 55 push bp

000004ED 8BEC mov bp,sp

000004EF EB47 jmp short 0x538 🔴 instead of checking the `while` condition, jump to the end

000004F1 90 nop

000004F2 C41E9005 les bx,[0x590]

000004F6 26837F2400 cmp word [es:bx+0x24],byte +0x0 🔴 check the `if` condition

000004FB 741F jz 0x51c

000004FD B8BA03 mov ax,0x3ba

00000500 50 push ax

00000501 E8BA09 call 0xebe

00000504 83C402 add sp,byte +0x2

00000507 A880 test al,0x80

00000509 74F2 jz 0x4fd

0000050B B8BA03 mov ax,0x3ba

0000050E 50 push ax

0000050F E8AC09 call 0xebe

00000512 83C402 add sp,byte +0x2

00000515 A880 test al,0x80

00000517 741F jz 0x538

00000519 EBF0 jmp short 0x50b

0000051B 90 nop

0000051C B8DA03 mov ax,0x3da

0000051F 50 push ax

00000520 E89B09 call 0xebe

00000523 83C402 add sp,byte +0x2

00000526 A808 test al,0x8

00000528 74F2 jz 0x51c

0000052A B8DA03 mov ax,0x3da

0000052D 50 push ax

0000052E E88D09 call 0xebe

00000531 83C402 add sp,byte +0x2

00000534 A808 test al,0x8

00000536 75F2 jnz 0x52a

00000538 8B4604 mov ax,[bp+0x4] 🔴 check the `while` condition

0000053B FF4E04 dec word [bp+0x4]

0000053E 0BC0 or ax,ax

00000540 75B0 jnz 0x4f2 🔴 go back up

[...]A familiar scenario repeats itself as with the previous loop - no matter what I try, the condition is placed at the end. I tried every single variant of the code, a for, a do-while, even a goto-based monstrosity. Same story. Optimization flags don’t have an influence except for /Od - disable optimizations. But in that case, the code is a complete mess that doesn’t look close to what I need either.

The problem this time is that it’s not enough to skip a couple of instructions. An entire code block is moved elsewhere. Unless I am willing to make the tool search for a match (not mentioning how to approach checking if a moved section will behave the same in a different location), or increase the allowed skip count, there doesn’t seem to be anything else I can do, and pushing ahead against an ever-increasing number of divergences doesn’t look feasible anymore.

I need to go back and figure out which compiler was used and with what flags. Without having that part down, I’m screwed. So I catch a deep breath and dive into it again.

First thing I tried was getting rid of the suspense and putting the Watcom question out of the way. I could not locate a copy of Watcom C 6.0/7.0 which appear to best match the release date of the game, so I tried the next best thing with OpenWatcom. Hopefully they did not change the code generation too much in 30+ years? The code it produced didn’t look close at all. I tried several optimization variants but there were just too many differences all over. In particular, test ax,ax was used instead of or ax,ax, multiple registers were pushed in preambles of functions, arithmetic registers were used instead of immediate values in instructions etc. Scratch that off, at least until I can find a copy of the old version, but I don’t think it’s a likely target.

The standalone versions of QuickC are still on the table. Version 1.01 was bundled with MSC 5.1 and I tried it in Part 2, but it produced horribly unoptimized code. Wikipedia says that QuickC was introduced as Microsoft’s answer to Borland’s Turbo C - an enthusiast-oriented compiler that is cheaper and a step down from the big-boy MSC. Turbo C produces quite neat code, so maybe the 2.x releases of Quick C are somewhat better if they want to compete with Turbo C? But at the same time it shoud not be too good, or I will end up with the same problems as with using the full-featured MSC right now. Well, no luck again, with no optimization flags it uses mov ax,0 instead of sub ax,ax which I need. With /Ot it uses xor ax,ax (and signedness of the argument it’s creating does not matter). It also puts a jmp short to a loop condition at the end and does some other weird stuff. It’s not the right one.

I had already tried MSC 5.0, 4.0 and 3.0 in hope that they perhaps differ somewhat in their generation of optimized code, but it turned out not to be the case. The difference is mainly in the language feature set supported by the newer versions - in particular, the older versions required function definitions to follow the ancient K&R style and were missing library functions which are now considered standard, but they still optimize loops in exactly the same way. MSC 2.0 is a different case however. It is basically a rebranding of the Lattice C compiler before Microsoft made their own thing with 3.0, so I was expecting its output to differ. Rightly so, it turned out, however again - not in the way I needed. It put the outer loop condition in the expected place, but the jump sequence was all wrong, more like QuickC with optimizations disabled. This was an interesting excursion, however. I never worked with a compiler which did not support the void type before. Also, there were some limitations on the use of whitespace, and the compiler itself worked in two passes. There are two executables, MC1.EXE and MC2.EXE. The output of the first is a .Q or “quad” file, and the other turns it into the expected .OBJ.

Now I’m really out of things to try. I mean, let’s be realistic, nobody at Microprose would decide it was a good idea to use an exotic compiler for a codebase that they’re just trying to tweak quickly and make a quick buck off of before the game is too old. So, no Digital Mars, DeSmet or anything of that sort. But maybe still Turbo C? Maybe I missed something. I spent some time trying to beat Borland C++ 3.0 and Turbo C 2.0 into submission again, since the output of those looked most promising. I lost and got a beating instead, same with MSC 6.0 revisited.

I was getting desperate, so I started reaching out to ex-Microprose employees that did not even work on F15 SE2 because I can’t get in touch with Andy Hollis. I was hoping I would learn something about how things were done at the company that could put me on the right track. Here’s what I was told by a person who worked on F117, which was the next iteration of the same engine after F15 SE2 (which itself built on top of F19):

- There was definitely no C++ used on the project. I was already suspecting as much, but it’s good to have it confirmed, because C++ would have complicated things.

- Sid liked gotos. The mission generation code used gotos extensively. Good thing to know, the code could diverge from the clean patterns of control that pure C provides and I’ll know that a goto is always an option.

- At that point in time, Microprose only used Microsoft C compilers/debuggers. After F117 they supposedly switched to Borland Turbo C, but the person I was talking to was “pretty sure” F-117 only used Microsoft C - so probably F15 did as well as the older game.

- They were also sure that the graphics code in F117 came from F15 SE2. There was no graphics programmer on F117, and every new project grabbed the latest and greatest graphics code available from another project - which would be F15 SE2 at the time F117 was being made.

Does that mean that what I’m seeing in the game binary is a product of MSC after all? But I tried everything I could with it. Or maybe the scenario disk version was an early pilot for the usage of Turbo C within the company? Grrr, so many possibilities. If I could just turn into a fly on the wall of a certain Maryland office building in 1991…

I start developing paranoia. Maybe my binaries are compromised. Maybe the LZEXE packer tweaks some instructions inside the binary. Maybe the unpacker did. Maybe, maybe. I see opcodes in the shower and the kitchen sink. It’s probably MSC. No, it can’t be MSC. My wife starts giving me concerned looks. She knows how I get when I have a puzzle to solve.

Let’s approach this from a different angle. Let’s say I’m working at Microprose in 1991, Bill Stealey comes in through the door and says “listen Junior, we need you to add a couple features to this game we released two years ago so we can squeeze a couple of extra bucks from it because Desert Storm just happened and I think we can capitalize off that. Make sure you don’t spend too much time, just get this over with quickly.”. What would I do?

Well, I definitely would not switch to a different compiler, or touch the build system at all. I would go in, add my changes, build them with debug flags, test and debug them, then when it’s good, I would rebuild with optimizations enabled, pass it to the production department and call it a day. Wait, the debug flags… what were they again for MSC?

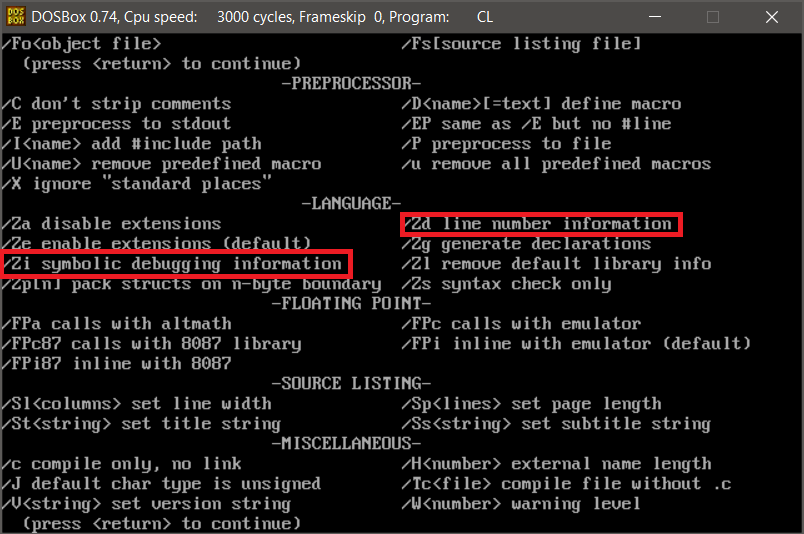

Doesn’t look useful, which is probably why I ignored them in the past. The game binary does not contain any symbol names that I can see. Meh, let’s try it anyway… holy shit!

ninja@dell:eaglestrike$ make verify --- build running cl from msc510 cl /Gs/Zi /Id:\f15-se2 /DMSC_VER=5 /c /Foe:\start.obj f15-se2\start.c f15-se2\start.c f15-se2\start.c(104) : warning C4021: 'openShowPic' : too few actual parameters f15-se2\start.c(121) : warning C4021: 'openShowPic' : too few actual parameters f15-se2\start.c(152) : warning C4021: 'openShowPic' : too few actual parameters f15-se2\start.c(253) : warning C4021: 'openShowPic' : too few actual parameters --- build running link from msc510 link /M /NOD start.obj start_o.obj slot.obj lowlvl.obj,d:\start.exe,,slibce.lib; ../mzretools/debug/mzdiff ida/start.exe:0x10 build-f15-se2/start.exe:0x10 --verbose --loose --map map/start.map Comparing code between reference (entrypoint 1000:0010/010010) and target (entrypoint 1000:0010/010010) executables --- Now @1000:0010/010010, routine 1000:0010-1000:0482/000473: main, block 010010-010482/000473, target @1000:0010/010010 1000:0010/010010: push bp == 1000:0010/010010: push bp 1000:0011/010011: mov bp, sp == 1000:0011/010011: mov bp, sp1000:0013/010013: sub sp, 0x1c =~ 1000:0013/010013: sub sp, 0xe 1000:0016/010016: push si == 1000:0016/010016: push si 1000:0017/010017: mov word [0x628c], 0x0 ~= 1000:0017/010017: mov word [0x5a0], 0x0 1000:001d/01001d: mov word [0x628a], 0x4f2 ~= 1000:001d/01001d: mov word [0x59e], 0x4f2 1000:0023/010023: mov word [0x45fc], 0x0 ~= 1000:0023/010023: mov word [0x598], 0x0 1000:0029/010029: mov word [0x45fa], 0x4f4 ~= 1000:0029/010029: mov word [0x596], 0x4f4 1000:002f/01002f: mov word [bp-0x10], 0x0 ~= 1000:002f/01002f: mov word [bp-0x04], 0x0 1000:0034/010034: mov word [bp-0x12], 0x4f0 ~= 1000:0034/010034: mov word [bp-0x06], 0x4f0 1000:0039/010039: les bx, [bp-0x12] =~ 1000:0039/010039: les bx, [bp-0x06] 1000:003c/01003c: mov ax, es:[bx] == 1000:003c/01003c: mov ax, es:[bx] 1000:003f/01003f: mov [0x77f4], ax ~= 1000:003f/01003f: mov [0x592], ax 1000:0042/010042: mov word [0x77f2], 0x0 ~= 1000:0042/010042: mov word [0x590], 0x0 1000:0048/010048: mov ax, es:[bx] == 1000:0048/010048: mov ax, es:[bx] 1000:004b/01004b: mov [0x4606], ax ~= 1000:004b/01004b: mov [0x59c], ax [...] 1000:00df/0100df: mov ax, 0x5 == 1000:00df/0100df: mov ax, 0x5 1000:00e2/0100e2: push ax == 1000:00e2/0100e2: push ax 1000:00e3/0100e3: call far 0x16b50be9 ~= 1000:00e3/0100e3: call far 0x10f701b9 1000:00e8/0100e8: add sp, 0x2 == 1000:00e8/0100e8: add sp, 0x2 1000:00eb/0100eb: sub ax, ax == 1000:00eb/0100eb: sub ax, ax 1000:00ed/0100ed: push ax == 1000:00ed/0100ed: push ax1000:00ee/0100ee: mov ax, 0x42 =~ 1000:00ee/0100ee: mov ax, 0x5c 1000:00f1/0100f1: push ax == 1000:00f1/0100f1: push ax 1000:00f2/0100f2: call 0x3312 (down) ~= 1000:00f2/0100f2: call 0x5ea (down) 1000:00f5/0100f5: add sp, 0x4 == 1000:00f5/0100f5: add sp, 0x4 1000:00f8/0100f8: call far 0x16b50c48 ~= 1000:00f8/0100f8: call far 0x10f70218 1000:00fd/0100fd: call 0x185a (down) ~= 1000:00fd/0100fd: call 0x616 (down) 1000:0100/010100: mov byte [0x76e], 0x0 ~= 1000:0100/010100: mov byte [0x5b0], 0x0 1000:0105/010105: cmp byte [0x76e], 0x78 ~= 1000:0105/010105: cmp byte [0x5b0], 0x78 😍😍😍 1000:010a/01010a: jnb 0x11e (down) == 1000:010a/01010a: jnb 0x11e (down) 1000:010c/01010c: call far 0x16b50c7a ~= 1000:010c/01010c: call far 0x10f7024a 1000:0111/010111: or ax, ax == 1000:0111/010111: or ax, ax 1000:0113/010113: jnz 0x11c (down) == 1000:0113/010113: jnz 0x11c (down) 1000:0115/010115: call far 0x16b50c7f ~= 1000:0115/010115: call far 0x10f7024f 1000:011a/01011a: jmp short 0x11e (down) == 1000:011a/01011a: jmp short 0x11e (down) 😍😍😍 1000:011c/01011c: jmp short 0x105 (up) == 1000:011c/01011c: jmp short 0x105 (up) 😍😍😍 1000:011e/01011e: cmp byte [0x76e], 0x78 ~= 1000:011e/01011e: cmp byte [0x5b0], 0x78 1000:0123/010123: jb 0x17c (down) == 1000:0123/010123: jb 0x17c (down) [...]

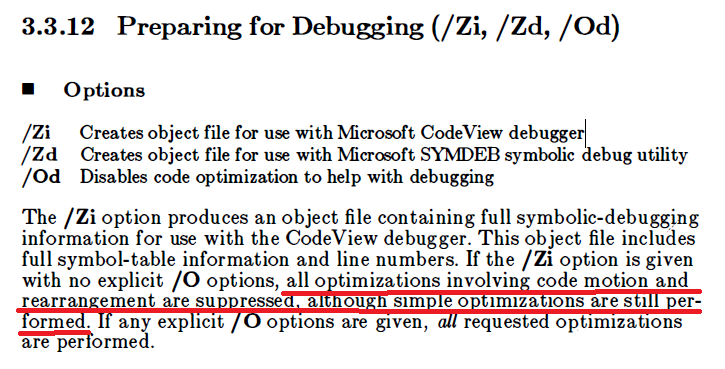

Using the /Zi option made the loop code with the superfluous jmp short-s match exactly even with a simple for loop - no questionable gotos required like when using Turbo C. What the hell does this option do exactly? Let’s consult the fine manual:

That explains everything. Unlike /Od which disables optimizations completely, /Zi just disables ones that make debugging difficult. And symbols are placed in the object files, not in the final executable which is why I can’t see them.

The commit history on my git repo for the reconstruction shows that I first hit the problematic loop for which I was unable to write C code that would exactly match the game’s opcodes on 29th March. It’s the end of August and I finally figured it out. Everything works now, there were a couple of divergences which were easy to tweak into 100% matching code. It’s actually eerie watching mzdiff display no skips and large swaths of exactly equal instructions, with only the occasional offset difference in orange.

So, did I just “waste” 5 months? No, I don’t think so. I learned a lot about how the compiler works and got a feel for the flow of opcodes and how they map to C code. I can now write easier conditions or loops as I read them. I can tell optimized from unoptimized code at a glance. It was extremely frustrating for a while, but the sense of satisfaction I got from finally finding the magic flag that somebody forgot to disable before making the final build is proportionally exhilarating. I managed to uncover a cool fact about the game, and it being (at least partially) built in debug mode means the instructions will be likely easier to follow.

It’s my own fault really for not RTFM’ing more carefully and assuming only the /O options could influence optimizations, but you have to admit that the option descriptions in the output of the compiler are misleading, to put it mildly. I recall searching the manual for all occurences of “optimization” at some point, but this is a scanned document and text search does not always work on it. Or maybe it did find the occurence, but I glossed over it after seeing “symbols”? Well, no point in wondering now. The project is back on track, I’m churning out functions like mad. I’m looking forward to being done with START.EXE and moving onto EGAME.EXE in the near future.